August Civic Holiday Has Origins in Alexandra Park

The August Civic Holiday is one of Canada’s oldest public holidays and predates Canada Day by six years.

Here’s how it originated at Toronto City Council:

In mid-19th century Toronto, there were few public holidays outside of the Christian holidays of Easter and Christmas. Sundays were reserved for religious purposes and had strict laws in place as to what citizens could and could not do. One of the few non-denominational public holidays was Victoria Day, which celebrated Queen Victoria’s Birthday each May and which Canada had adopted as an official holiday during the mid-1850s. Following Victoria day, the idea of additional public, non-denominational holidays had begun to spread.

In the first week of September 1861, John Carr — serving as a local alderman at City Council for St. Andrew’s Ward and later St. Patrick’s Ward — introduced the following motion to City Council:

"Be it resolved that in order to afford the citizens an opportunity for relaxation and enjoyment, His Worship The Mayor be requested to proclaim a Public Holiday at as early as a day as he may think convenient."

Debate immediately arose as to whether the City could afford such a Public Holiday, as merchants and residents were busy preparing for the fall including processing harvest-related shipments. Proposals were also brought forward that the Councillors and Aldermen should have a cricket match against each other on the holiday.

The motion passed at City Council 19 to 5. The Mayor subsequently proclaimed Thursday, 12 September 1861 the first of the Public Holidays.

The first of these holidays was not widely celebrated.

The Globe reported that only about a dozen stores on King Street and Yonge Street — then the commercial heart of the City — opted to close and that business and municipal activities largely carried on as normal. A few citizens with the day off coordinated large group picnic trips to Hamilton, Niagara Falls, and Weston.

The newly established horse-drawn streetcar service — a source of significant debate in 19th century Toronto, particularly as to whether it should run on Sundays and holidays — also ran its normal routes and schedules much to the chagrin of City Council.

In its early years, the holiday shifted around depending on the discretion of Toronto City Council and the official date was not announced until the Council had voted on it. This was followed by a Mayoral Proclamation formally announcing the date of the holiday — often made only a week or two beforehand.

Whereas the holiday occurred in early September in 1861, Council voted the following year, in 1862, to celebrate it in mid-August with significant debate arising as to whether to celebrate it on Monday the 18th or Tuesday the 19th.

Some years — such as 1864 — also required a petition from ratepayers before Toronto Council would vote on whether to have a holiday.

The ever-changing date of the holiday and the last-minute mayoral proclamation announcing the actual date for celebration fuelled frustration for some business owners.

In an August 1957 retrospective examination of the holiday (“Holiday Has Hectic History”), The Globe and Mail notes that by the late 1860s, Toronto business owners had begun to revolt over City Council meddling in the “natural course of business affairs” and were calling the holiday The Forced Holiday.

In 1868, 44 businessmen coordinated a protest of the holiday, but later withdrew their protest less than 48 hours before the holiday.

By the early 1870s, controversy around the holiday had waned. In 1875, the first Monday of August was adopted as the standard date for the holiday.

In 1871, the holiday gained the attention of the British Parliament who were looking to introduce a midsummer holiday in the United Kingdom. Sir John Lubbock favourably viewed Toronto’s holiday and included reference to it in debates around the Bank Holidays Act of 1871. This Act sought to provide additional holidays for the public and through the Act it later spread to other colonies of the British Empire, including Australia.

By 1939, the holiday had been adopted in cities in Western Canada, including Edmonton and Regina. Eventually the name changed from "The Public Holiday" to “Civic Day.”

During the 20th century, the holiday began to change its identity with many municipalities assigning honorific names to the day to celebrate influential historical figures within their district. In 1969, Toronto voted to rename the holiday Simcoe Day in honour of John Graves Simcoe, the first Lieutenant-Governor of Upper Canada. Simcoe was also a strong supporter of abolition and championed the Act Against Slavery. Elsewhere in Ontario, municipalities adopted other names for the holiday — its known as Joseph Brant Day in Burlington, Peter Robinson Day in Peterborough, and Colonel By Day in Ottawa — among others.

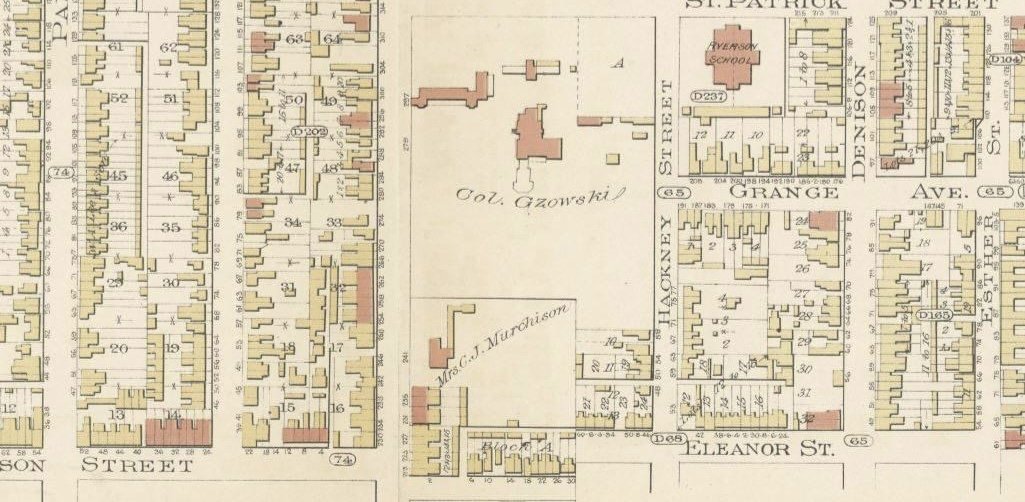

John Carr’s house on Denison Avenue, near Queen Street West — where he lived when the first Civic Holiday was proposed and enacted — still stands to this day. Elizabeth Street — an east-west street in Alexandra Park — was later renamed Carr Street in his honour.

Interested in learning more about the history of the August Civic Holiday and Toronto history? The author invites you to a free neighbourhood walking tour “From Alexandra Park to Trinity Bellwoods” this weekend— supported by Friends of Alexandra Park and West Queen West BIA. Details below:

Tour #1: Sunday, 6 August 2023 at 2.00 PM

Tour #2: Monday, 7 August 2023 at 10.30 AM